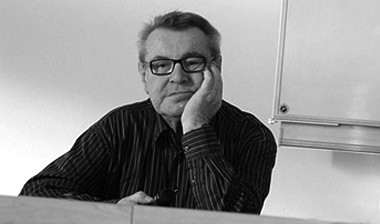

Miloš Forman

INSIDE THE LIFE OF FORMAN

“I believe that we decipher the incoherent flow of life through stories. The stories may not add up to much, they may end abruptly or proceed according to mysterious logic, but my kind of film has to have them.”~ Miloš Forman

Miloš Forman’s life is filled with stories—triumphs and tribulations. Throughout some of his most difficult times, he persevered to accomplish his dream of making movies, becoming an award-winning Czech legend, and a renowned and respected Hollywood director. On his road to success, he met struggle, failure, box office disaster, but also a host of friends and an incredible drive within him that helped support him, his vision, and his success.

CHILDHOOD - What the movie is about...

Jan Tomáš Forman, popularly known as Miloš Forman, was born on February 18, 1932 in Čáslav, Czechoslovakia (present-day Czech Republic) and raised by his mother Anna, who ran a summer hotel at Mácha’s Lake, and Rudolf Forman, a professor. He grew up with two brothers, Blahoslav and Pavel, and was the youngest by twelve years. The first film he saw with his parents was a silent documentary on the famous Czech opera The Bartered Bride. Since the opera was so popular, the people in the audience started singing along to the silent film. Forman recalled, “And for me, that’s what the movies were about. You show some photographs and people sing.” As a young boy, he also fell in love with such American classics as Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. After World War II, he saw many silent films, and these films were instrumental in his passion for movie making, including films by Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Laurel and Hardy, and Harold Lloyd. Little did he know that he would one day become one of the world’s most famous directors not only in his homeland, but also Hollywood—the heart of American filmmaking. Photo courtesy of FAMU.

ORPHAN - Flow of life through stories

When Forman was seven, he was called out of class to see his father standing with two Gestapo men. His father’s pleasant demeanor disguised the seriousness of the situation. He told him to do his homework and give his mother an envelope. Forman did not understand why his mother burst into tears upon reading the letter inside. After serving in prison for being a part of a Czech Resistance group which distributed banned books, Rudolf Forman was called in front of a judge that said he could be released on time served; he never was released. Then, Forman witnessed his mother being taken away. At ten-years-old, Forman was in bed with a fever when he heard a knock at the front door, men’s voices, and draws slamming. The Gestapo entered and searched the house. His mother was taken away along with 12 other women from the village. Eleven of the women returned to the village. She never did. Forman later found out that the Gestapo man who had stamped his mother and father’s file “Return Nondesirable” had once worked for his family on their summer hotel. Both his parents perished in concentration camps. Forman later found out that his biological father was a Jewish architect named Otto Kohn. He had worked on the family’s summer hotel. During the war, he moved to South America. After finding out about his father, Forman tried to reconnect with him, but it never worked out.

Photo courtesy of Oldřich Škácha

SURVIVOR - How to read people's minds

Forman lived much of his life out of a suitcase, transported from relatives to family friends. He was first sent to live with his Uncle Boleslav who owned a grocery store in Náchod. While in the store, he listened to people’s conversations, savored the scent of roasted coffee, munched on sauerkraut that he would sneak from a barrel, and admired the beautiful housemaids. He later drew on the experiences for his first feature-length film Black Peter. Later, he was sent to live with his Aunt Anna whose husband owned an apothecary, which delighted his nose with delicious fragrances. While there, he learned to appreciate books by such legendary authors as Jules Verne, Victor Hugo, and American legendary author Mark Twain. By being shuffled from relatives to family friends, he tried extra hard to never be a burden. He learned to read people’s moods and understand their feelings. In his autobiography Turnaround he states, “I didn’t know it at the time, but I see now that living out of a suitcase gave me very good training for my future trade as a director.”

Photo courtesy of Oldřich Škácha

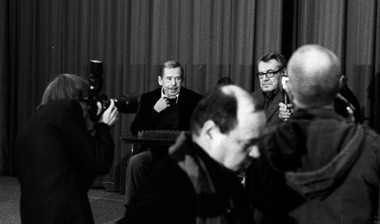

FRIENDS - For life and film

After the war, Forman attended high school at the King George College Public School, established by the government for war orphans in a 15th century castle in the spa town of Poděbrady near Prague. He was surprised to discover that many of the students were not orphans but sons of elite society members. The boarding school had received numerous grants and a lot of funding and became one of the best schools in the country. During his time at school, he watched numerous French, Russian, and American films, including the Westerns of John Ford, and formed lasting friendships that left an indelible impression on his life. His closest friends included Ivan Passer, who would later become a successful film director, and Václav Havel, who became the leader of the Velvet Revolution and the President of the Czech Republic. Years later, when Havel was imprisoned by the communists, he used to dream about Forman and what a success story he was as a film director. Havel had wanted to become a director too; his father and uncle founded Barrandov Studios, one of the largest and oldest film studios in Europe, modeled after Hollywood. Forman and Havel planned on making a film together, the Ghosts of Munich, but it never came into fruition. Photo courtesy of Oldřich Škácha

LIFE DECISION - To be a director

Before the end of WWII, Forman’s brother Pavel worked as a set designer for the East Bohemian Operetta and took Forman for his first theatrical experience. Forman spent the evening in the ladies’ dressing room, equating them with goddesses, and watching the flurry of activity unfold. Particularly, he observed how these goddesses all paid attention to one man, a sort of “super god.” His brother informed him that he was the director, and Forman decided on the spot that he wanted to be a theater director. To become a theater director, Forman planned on attending the Academy of Dramatic Arts in Prague; however, he was not accepted. During his entrance exams, he was asked to direct the struggle for world peace, but his mind went blank. He was so sure that he would get into the program that he had no backup plan. In order to dodge military service if he were not in school, he applied to the only departments of schools still accepting applications―mining and engineering, law, and film. He took the entrance exams for the film academy and was accepted into the screenwriting program. This fork in the road would lead him to becoming one of the most renowned film directors in the world.

Photo courtesy of Oldřich Škácha

STUDENT - Developing film passion

Forman attended the Film and Television Academy of the Performing Arts in Prague (FAMU), which today is rated by the Hollywood Reporter as the best film school in Europe. At the film academy, he studied screenwriting under the famous Czech novelist Milan Kundera, who made him read such books as Les Liaisons Dangereuses by Choderlos de Laclos. The novel left such an impression on him over the years that he later based his movie Valmont on an adaptation of the novel. At school, he also enjoyed the opportunity to see “controversial films” that the general public was banned from seeing and would stay up late at night conversing about the films with his friends. He saw for the first time Miracle in Milan, which became one of his favorite films of all time. The film fascinated him. He enjoyed seeing so many real people on the screen–90 percent of the people in the film were regular people in the background or on the street. Film school enabled him to develop his passion and see a range of films that became a foundation for his filmmaking.

Photo courtesy of Oldřich Škácha

APPRENTICE - Falling in love with directing

As an apprentice, Forman worked on a host of different projects before he “made it” as a film director. He worked with famous Czech director Martin Frič on a screenplay called Leave It Up to Me, which garnered him one of the biggest paychecks at that time. By twenty-three, he helped develop screenplays for Alfréd Radok on films including Distant Journey, and served as the second directorial assistant on Radok’s film Grandpa Automobile. Radok handed over the reigns of director to Forman for the first time during a scene in the movie, and Forman fell in love with directing. He later worked with Radok on Laterna Magika (Magic Lantern), a new media show incorporating dance, theater, and film, which enabled him to travel abroad to the 1958 Brussels Exposition. Laterna Magika received the gold medal at the Expo and even Walt Disney stopped by the pavilion to tell them he admired their work. While in Brussels, Forman spent most of his time at the American Pavilion completely taken by jazz legend Ella Fitzgerald, Jerry Robbins’ choreography, and American singer Harry Belafonte.

Photo courtesy of Jaromír Komárek

CINEMATIC RELATIONSHIP – Finding his cameraman

To learn more about the film business, Forman decided to cash in his savings and buy a 16 mm German camera, but did not know how to use it. His friend Ivan Passer introduced him to Miroslav Ondříček, an assistant cinematographer at Barrandov. This man would become Forman’s lifelong cameraman who shot many of his films, including Amadeus and The People vs. Larry Flynt. They established their cinematic relationship filming a “home movie” of a pop-music cabaret theater called the Semafor Theater. With that footage, Forman went to the Šebor-Bor production team, who would later oversee all Forman’s Czech films. They asked him to expand the film into a 15-minute short, and he came back with 45 minutes. The only way his film, which became known as Audition (Konkurs), could be distributed was with the addition of another short to make a feature-length show. Hence, Kdyby ty muziky nebyly (If There Were No Music), a film about brass bands, was added and packaged together. This was his first major step into the realm of directing.

Photo courtesy of Jaromír Komárek

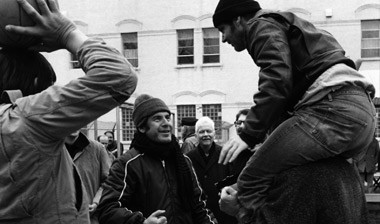

CZECH NEW WAVE - Director

Forman developed a desire to be a director when he saw what directors would do with his scripts. His style was influenced by elements of cinéma vérité and his early films Black Peter (Černý Petr), Loves of a Blonde (Lásky jedné plavovlásky), and The Fireman’s Ball (Hoří, má panenko) made him a leader of the Czech New Wave, an artistic movement of the 1960s hailed as the “golden era” of Czechoslovakia’s cinematic history. Trademarks of the movement included long unscripted dialogue, dark and absurd humor, and the casting of nonprofessional actors. A frequent feature of the films was an interest in the concerns of ordinary people, particularly when faced with historical or political challenges. The core of the new wave was made up of recent graduates of the Film and Television Academy of the Performing Arts (FAMU) in Prague and defined by a relatively small group of directors who made their debuts in or around 1963, including Jiří Menzel whose film Closely Watched Trains (Ostře sledované vlaky) won an Academy Award for Best Foreign Picture and Věra Chytilová who is best known for her film Daisies.

Photo courtesy of Jaromír Komárek

LEAVING CZ - First US Experience

When the Soviet tanks rumbled into Prague in August 1968, Forman was in Paris negotiating to make his first American film, Taking Off. He later traveled to New York to finish the script and planned to return home to Czechoslovakia. While pursuing the film, the Czechoslovak government said that he was out of the country illegally and the studio fired him. On top of being alienated by his homeland, Forman’s first American filmmaking endeavor proved to be a total flop. Although critics praised the film, Forman ended up owing Universal $500. After the flop of Taking Off, Forman resided at the Chelsea Hotel and was thankful for the generosity of its manager, who allowed him to stay there for over a year until he was finally able to pay back the rent. The hotel was home to a host of painters and artists, and over the years, including such luminaries as director Stanley Kubrick, writers Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams, and musician Bob Dylan. Forman lived on about $1 a day, with a daily diet consisting of a can of chile con carne and a bottle of beer. On the brink of a nervous breakdown, his friend Ivan Passer would go to the psychologist pretending that he was Forman to help his friend.

Photo courtesy of Oldřich Škácha

IT WAS FATE - Best Director

Kirk Douglas was in Prague on a Goodwill Mission and was shown Forman’s film Loves of a Blonde. Douglas asked if he could send Forman a book (Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) and if he would be interested in making a movie in America. Forman said yes but never received the book because it was confiscated by the communist censors. Ten years later, Kirk’s son Michael Douglas sent the book to Forman when he was living in the Chelsea Hotel in New York. Forman read the book and agreed to direct the film, which swept five of the top Oscars beating out director Steven Spielberg’s Jaws for best picture. Forman also won his first Oscar for Best Director, over nominees such as Federico Fellini, Stanley Kubrick, Sidney Lumet, and Robert Altman. Made on a $4.4 million dollar budget, the film has gone on to gross more than $320 million worldwide. Gene Hackman and Marlon Brando both passed on the lead role which garnered Jack Nicholson an Oscar for Best Actor. The success of the film catapulted Forman’s career, and opened a number of doors for him, giving him more freedom to make the films he wanted to make.

Photo courtesy of The Saul Zaentz Company

AMADEUS - Professional Triumph

One evening when Forman was in London casting his film Ragtime, when his agent, Robert Lantz, who also represented playwright Peter Shaffer, called and asked him if he wanted to see a new play. Forman agreed to see the play, but was so busy with casting that he didn’t even ask what they were going to see. When he found out that they were going to see a new play about a composer, he was prepared for the most boring evening ever. As he was waiting to fall asleep in the theater, the performance started and he was surprised to find a wonderful drama unfold. He believed that it would make a wonderful film - Amadeus. After the show, he met the playwright, Peter Shaffer, and he agreed to work with Forman on developing the screenplay. Filmed almost entirely on location in Forman's native homeland, Amadeus was his first film made in Czechoslovakia since his emigration in 1968 to the United States. Although Miloš Forman has made numerous award-winning films, one of his most triumphant successes was Amadeus. The film was nominated for 54 awards and won 41, including 8 academy awards.

Photo courtesy of Jaromír Komárek

www.mzv.cz/washington