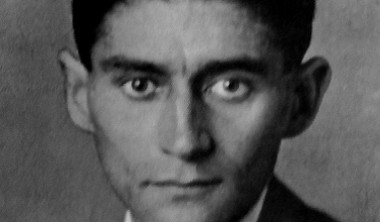

Franz Kafka

FRANZ KAFKA

“All I am is literature, and I am not able or willing to be anything else.” ~Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka (1883–1924) resonates throughout history as one of the most influential writers of the 20th century. Hailing from Prague, he was born to a middle-class, Geman-speaking, Jewish family. He studied law, yet regretted having to devote so much of his time working for an insurance company. Above all, his calling and passion was writing, which he pursued in his free time, primarily in the evening hours after working a long day. During his lifetime, he published a handful of stories, dealing with themes such as isolation and alienation. On his deathbed, he asked his friend Max Brod to burn most of his writing. Instead, Brod completed and published a large body of his work, leaving an impression of the Kafka that we know today. Kafka has influenced such writers as Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Eugène Ionesco and the genre of existentialism. Some of his most widely read works include The Metamorphosis, A Hunger Artist, In the Penal Colony and The Judgment. His writings transcend time and, as in the case of his longer work The Trial, even foreshadow future events. Kafka was a genius of literature―using the power of words to convey the images released from his very soul. He had a gift that he could not deny, calling his writing a form of prayer.

Photo: Franz Kafka’s passport photo

HERMANN KAFKA

“What I needed was a little encouragement, a little friendliness, a little help to keep my future open, instead you obstructed it, admittedly with the good intention of persuading me to go down a different path.” ~ Franz Kafka, Letter to My Father

Kafka’s father, Hermann Kafka, worked his way up from poverty. As soon as he was able to push a wheelbarrow, he began delivering kosher meats for his father. He left home at the tender age of fourteen, joined the army at nineteen, and then took on employment as a traveling salesman. He had a strong work ethic, eventually becoming owner of a retail store for men’s and women’s accessories where he used a black crow-like bird called the jackdaw (Kavka in Czech) as his business logo. He also established himself through an advantageous marriage to Julia Löwy, who was better educated and the daughter of a prosperous brewer. As the business grew, Hermann had high blood pressure, as well as respiratory and cardiac problems; therefore, the family worked hard not to excite him. He especially did not like humor at his own expense and often expressed his disapproval of Franz’s passion for writing, pressuring his son to take over the family business. Throughout his life, Kafka was overwhelmed and intimidated by his domineering, tyrannical father. Kafka’s troubled relationship with him is documented in his over 100-page Letter to My Father, which Kafka’s mother advised Kafka never to give him, as well as his short stories The Judgement and The Metamorphosis. Kafka wanted love and encouragement, but he felt abandonment as his parents worked long hours trying to run the business.

Photo: Kafka’s father Hermann Kafka and his mother Julie (Löwy)

PRAGUE

“Prague never lets you go… this dear little mother has sharp claws.” ~Franz Kafka

Prague, the city of 1,000 spires, was the home to the legendary writer Franz Kafka, born on June 3, 1883, near the Church of St. Nicholas. Although he never directly referred to the city in his writing, his letters and fictional works reflect his life’s experiences and surreal thoughts within this mysterious maze of cobblestone streets. His virtual footprints are left throughout the city as his family moved numerous times over the course of his childhood. As a boy, Kafka lived in the Minute House, currently part of the Town Hall in Old Town. He also later had a modest apartment within the building that now houses the American Embassy. With friends, Kafka would go to local coffee houses, such as the Café Louvre, to discuss intellectual ideas. He held the first public reading of his work The Judgement at Hotel Erzherzog Stefan, today known as The Grand Hotel Europa, situated in Wenceslas Square. For entertainment, Kafka and his friends would attend cabaret performances and cinema screenings at Lucerna. To find a peaceful respite for his writing, he wrote at his sister’s house located on the Golden Lane in Prague, House No. 22. The city housed his inner turmoil, served as the backdrop for his struggle against totalitarian bureaucracy, and held his secrets amidst its labyrinth.

Photo: Old Jewish Quarter in Prague

ELLI, VALERIE, and OTTILIE

“Youth is happy because it has the ability to see beauty.

Anyone who keeps the ability to see beauty never grows old.” ~ Franz Kafka

Kafka was raised primarily by governesses and servants while his father worked hard on his thriving business at a haberdashery alongside his mother. He was the eldest of six children―two brothers died in infancy, and he had three sisters Gabriele ("Elli"), Valerie ("Valli"), and Ottilie ("Ottla"). Although he was rather withdrawn even as a child, Kafka dearly loved his little sisters and found time to read and write various plays for them. He would serve as the director and his sisters the actors for his plays acted out on the occasion of his parents’ birthdays. His youngest sister Ottla was his favorite. When they grew into adulthood, she was a close confidant and took care of him at times when he fell ill. As a child, she would get up early to open the shop for her father’s business, but she greatly desired her independence from him. Therefore, she went to live and work on the farm of her brother-in-law in Zürau (now called Siřem), located in Western Bohemia. Kafka sometimes would go to visit her, finding a refuge to write. From September 1917–April 1918, Kafka stayed on the estate with her, already suffering from tuberculosis. Kafka called her “the love to the others notwithstanding, the dearest by far.” All three of his sisters outlived Kafka, but they perished in the Holocaust.

Photo: Kafka at about ten with his sisters Valli (left) and Elli (center)

EARLY YEARS

“First impressions are always unreliable.” ~Franz Kafka

For his early education, his parents decided to send him to the German-speaking elementary school Deutsche Knabenschule on the street now known as Masná Street in Prague. After elementary school, he was admitted to the rigorous state gymnasium, Altstädter Deutsches Gymnasium, an academic secondary school where German was also the language of instruction, in the Old Town in Prague. In his leisurely time, Kafka enjoyed swimming, rowing, hiking, often taking his healthy activity to the extreme. In later years, he would go to sanatoriums for fresh air and naturalist remedies to deal with his ailing body. Besides outdoor activities, Kafka also liked to attend the cinema, seeing such films as the Western Slaves of Gold, Little Lolette and even Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid. In his early journals, he wrote about his fascination with cinema stating, "Went to the movies. Wept. Matchless entertainment." Above all else, though, he preferred quiet writing. This proved difficult when living with his father’s outbursts, a full household, and the family’s pet canaries. He often suffered from migraines and was extremely sensitive to noise.

Photo: Kafka at around the age of 18 years old.

SCHOLAR

“Many a book is like a key to unknown chambers within the castle of one’s own self.” ~Franz Kafka

Kafka wrote, “Books are a narcotic.” He was an avid reader devouring the writings of such philosophers as Friedrich Nietzsche and Baruch Spinoza, Russian dramatist and short story writer Anton Chekhov, the early works of Thomas Mann, and even Charles Dickens. He especially enjoyed reading biographies, such as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe―a poet and philosopher of the Age of the Enlightenment―as well as the Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. Kafka considered his literary “blood-relatives” to be French writer Gustave Flaubert, Russian novelist and writer Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky, German poet, dramatist, and writer Heinrich von Kleist, and Austrian writer and dramatist Franz Grillparzer. Kafka breathed in their works and personal writings. He also attended various lectures, including Albert Einstein´s lecture on the Theory of Relativity. For his studies, Kafka went to Charles University in Prague, initially choosing chemistry and German studies before switching to law two weeks later because he felt it would not interfere as much with his creative pursuits—writing. Upon completing his law studies, Kafka took on employment with an Italian insurance company, switching a year later to work for the Worker's Accident Insurance Institute for the Kingdom of Bohemia, where he investigated personal injury claims. The parnassah (“job for bread”) allowed him spare time to write works such as The Castle and The Trial, both novels being about oppression and struggle against bureaucracy.

Photo: Kafka as a doctorate of law, around 1906

MAX BROD

“A non-writing writer is a monster courting insanity." ~ Franz Kafka, Letter to Max Brod, July 5, 1922

While at Charles University, Kafka participated in a student literary club, which organized literary events, readings and other activities. Here, he met lifelong friends Felix Weltsch, Oskar Baum, Franz Werfel and his closest friend who would later serve as his literary executor—Max Brod. The group became known as the Prague Circle (Der Prager Kreis), a name coined by Brod, reflecting the close-knit group of German-language writers from Prague with common cultural and literary values. According to Brod’s biography of Kafka, they met at a lecture that Brod gave on the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, during which Kafka objected to Brod’s characterization of Nietzsche as a fraud. Kafka waited almost two years before showing him any of his writing. As their friendship grew, Kafka could stop at Brod’s house at any hour unannounced. They would read their works to each other for hours on end and write to each other when away. Brod and Kafka also travelled together. Kafka even wrote the intro to a travelogue with Brod, but the writing collaboration stopped there simply because their styles were too different. Brod encouraged Kafka to write and publish his work, seeing his remarkable gift with words. Kafka dedicated a series of his first published works in a collection called Meditation to M.B. – Max Brod. He entrusted Brod with his dying wish of destroying all of his unpublished work, which Brod refused to do. Instead, he completed and reorganized Kafka’s three novels, letters, and diaries and saved them from the Nazis by taking them in a suitcase to Palestine where he later published them. Ironically, although Brod was a more prolific and established writer at the time, history remembers him primarily as Franz Kafka’s biographer and literary executor.

Photo: (from left to right) Max Brod with Kafka

IDENTITY

“I am a cage, in search of a bird.” ~ Franz Kafka

Kafka struggled constantly with his very self, never feeling that he or his work was good enough. He was self-analytic, self-obsessed—an introvert. His demeanor was quiet and reserved. His daily routines included rigid hygienic standards, every morning washing, combing his hair and shaving a particular way, usually leaving him late for work by 15 minutes every day. At close to six feet tall, he only weighed about 115 pounds and often wore dark blue suits. Although he did not consider himself handsome, others found him with boyish good looks. Once achieving his doctorate in law, he was even mistaken for a school boy. Kafka maintained a strict vegetarian diet. He had the habit of fletcherizing, chewing his food slowly and grinding it before swallowing. He did not smoke or drink, and stayed away from coffee, tea, and animal fat. A typical breakfast with his family consisted of pastries, milk, and stewed fruit. Although he never married, Kafka held marriage and children in high esteem, but sentenced himself to bachelorhood due to what he saw as his many imperfections and his desire not to be like his father. He had a mixed relationship with women—engaged twice, a couple of affairs, and numerous visits to Prague’s red light district. Some scholars even question his sexuality. The more one reads Kafka, the more one contemplates, returns to him and his work, and uncovers a piece of the puzzle only to start anew. Kafka was complex, deep, and emotional.

Photo: Kafka at the age of 27 years old.

FELICE BAUER

“You are at once both the quiet and the confusion of my heart; imagine my heartbeat when you are in this state.” ~Franz Kafka, Letters to Felice

Kafka wrote over 500 letters to Felice Bauer, which were published many years after his death as Letters to Felice. He was twice engaged to her. The two had met one evening when Kafka was visiting his friend Max Brod to go over the order of his upcoming volume of short works entitled Meditation. In his diary, he wrote the following about his impression of her, “I was not at all curious about who she was, but rather took her for granted at once. Bony, empty face that wore its emptiness openly. Bare throat. A blouse thrown on. Looked very domestic in her dress although, as it turned out, she by no means was.” This does not appear as the most flattering analysis, but Kafka had a habit of seeing life in its pure form. Something drew him to her. Perhaps, it was that she surprised him with her independence, confidence, and perspective—especially her interest in Hebrew and traveling to Palestine. The evening that they met, they made a pact to travel together to Palestine, but it never came into fruition. They did not meet again for seven months, but fell in love via mail. Over the next five years, while seldom in the same city, they became engaged, broke their engagement, became engaged again and finally broke up forever. During the period of his correspondence with her, Kafka produced some of his most famous works, including The Metamorphosis, In the Penal Colony, and his first draft of The Trial. He dedicated to her his short story The Judgement, which he wrote in one sitting. Kafka burned her letters to him, but she kept his. In 1955, Felice sold the letters to Schocken Books for $8,000 near the end of her life. At auction in 1987, the Letters to Felice brought Shocken Books over half a million dollars.

Photo: Felice Bauer and Franz Kafka in Budapest, 1917

YITZHAK LÖWY

“Anything that has real and lasting value is always a gift from within.” ~Franz Kafka

Around the time of 1911, Kafka became interested in Yiddish theatre, despite the misgiving of his close friends such as Max Brod who usually supported him in everything else and the vehement disapproval of his father. Kafka attended over 30 performances of the traveling theatre group in the seedy, rundown Café Savoy, befriending Polish actor Yitzhak Löwy. The performances served as a starting point for Kafka’s growing relationship with Judaism. Kafka even organized evening readings of Yiddish literature and gave opening remarks, although these brief remarks would leave him with sleepless nights because of his stage fright. Yizak spoke to Kafka about Jewish life in Poland and brought him in contact with a wide range of Yiddish literature. During his exploration of Yiddish theater, Kafka began to study Hebrew, and became more interested in Eastern Judaism and his own Jewish origin. He also began to write the novel The Man Who Disappeared, later Brod renamed it—Amerika, referencing a place Kafka only viewed through the letters of his uncles and in journals.

Photo: Yitzhak Löwy

MILENA JESENKÁ

“I see you more clearly, the movements of your body, your hands, so quick, so determined, it's almost a meeting, although when I try to raise my eyes to your face, what breaks into the flow of the letter...is fire and I see nothing but fire.” ~Franz Kafka, in a letter to Milena Jesenská

Milena Jesenká was a Czech journalist, writer and translator who married Jewish literary critic Ernst Pollak. Her father put her in an insane asylum for nine months to try to deter the union, but the two ended up wed and she in an unhappy marriage. Trying to supplement her income, she met Kafka while working as a translator. Initially, she had discovered Kafka’s short story, The Stoker, and asked him if she could translate it from German into Czech. He agreed and she became the first translator of his work into Czech and any foreign language for that matter. Their relationship was conducted mainly through letters which they first exchanged in German. He later insisted that she write in Czech so that he could capture her whole persona through her native tongue. Kafka and Milena met in person only twice, the longest span was for four days in Vienna. He eventually broke off the correspondence because Milena was unable to leave her husband. After Kafka’s death, she published an obituary in Národni Listy saying that he was “condemned to see the world with such blinding clarity that he found it unbearable and went to his death.” After the annexation of the Sudetenland, Milena worked to help her Jewish friends escape Czechoslovakia. She was later captured and deported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, where she died three weeks before D-Day. Today, in Prague, Café Milena is named after her.

Photo: Milena Jesenská

DORA DIAMANT

“It is entirely conceivable that life’s splendor forever lies in wait about each of us in all its fullness, but veiled from view, deep down, invisible, far off.” ~Franz Kafka, written in his diary on October 18, 1921

While vacationing at a Baltic Sea resort, Kafka met Dora Diamant, a 25-year-old kindergarten teacher from an Orthodox Jewish family, who was independent enough to have escaped her past in the ghetto. It was love at first sight, and they ended up spending every day of Kafka’s three-week vacation together. Kafka later moved to Berlin to live with her, and she became his lover. She influenced Kafka's interest in the Talmud, the basis for all codes of Jewish law. During their time together, Kafka managed to write A Little Woman and The Burrow. In their conversations, Dora and Kafka often spoke about moving to Palestine, where he would open up a restaurant with Dora and work as a waiter. However, this dream never came into fruition. As his health deteriorated, she helped Kafka burn some of his writings. Kafka is said to have died in her arms on June 3, 1924. His body was ultimately brought back to Prague where he was interred on June 11, 1924, in the New Jewish Cemetery in Prague-Žižkov. Secretly, Dora had kept a number of Kafka's notebook and letters. They were stolen from her apartment by a Gestapo raid in 1933 and attempts to find them have been to no avail. Even after Kafka died, she never gave up her dream of traveling to the Promised Land. In 1950, she finally realized her dream and visited the new state of Israel. She died two years later.

Photo: Dora Diamont

KAFKAESQUE

“I write differently from what I speak, I speak differently from what I think, I think differently from the way I ought to think, and so it all proceeds into deepest darkness.” ~ Franz Kafka, in a letter to his sister Ottla

Kafka died of laryngeal tuberculosis, which made it very difficult for him to eat. He died just a few days short of his 41st birthday. On his death bed, he was proofreading A Hunger Artist about a performer who would fast for days but eventually was ignored by the passing public. His writing legacy continues to live on thanks to his friend Max Brod, as well as the others who saved pieces of his work. Although his death came at a young age, his name is celebrated with the best authors of all time. He is known for his writing style about the absurdity of life in bizarre even nightmarish situations, giving rise to today’s term “Kafkaesque.” The term has been used in the English language for over 50 years and has become a staple ingrained in everyday vocabulary. Today, in Prague’s Jewish Quarter, stands a monument in salute to Kafka. The sculpture shows a suited Kafka on the shoulders of a gigantic headless man – a surreal tribute to the writer. However, his lasting legacy is his words, which continue to challenge readers and bring insight to future generations. No other author of modern times has left such an impact with his name.

Photo: Franz Kafka, last portrait, 1923

www.mzv.cz/washington