Karel Čapek

KAREL ČAPEK

“Nothing is stranger to man than his own image.” ~ Karel Čapek, R.U.R.

This year marks the 125th anniversary of the birth of Czech writer Karel Čapek (January 9, 1890 – December 25, 1938). Known as a playwright, novelist, short story writer, journalist, children’s author, biographer, and essayist, he wrote on such topics as nationalism, totalitarianism, and consumerism. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature and called a forerunner to such renowned science fiction writers as George Orwell and Aldous Huxley. His plays appeared on Broadway soon after debuting in Prague, and his books have been translated into many languages. He wrote his most renowned play R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots), which made famous the word “robot” and centers on machines dominating the human race with the threat of extinction. Many of his works debate ethical aspects of industrial inventions including mass production, nuclear weapons, and artificial intelligence. Čapek is noted for his influence on modern Czech literature as well as the development of Czech as a written language. Through his unforgettable works, he expressed his concern for violence in the world, absolute power, and greed, trying to find hope through humor and warning his countrymen of a looming darkness that culminated in WWII.

Photo Courtesy: Karel Čapek Memorial

Karel Čapek

CHILD

“It was a great thing to be a human being. It was something tremendous. Suddenly I'm conscious of a million sensations buzzing in me like bees in a hive. Gentlemen, it was a great thing.” ~ Karel Čapek, R.U.R

Karel Čapek, the youngest of Antonín and Božena’s three children, was born on January 9, 1890, in Malé Stratoňovice, a mining town located in present-day Czech Republic. He had an older sister Helena (born in 1886) and an older brother named Josef (born in 1887), with whom he often collaborated on his writings. His hard-working, rigorous father was a country doctor. In his spare time he gave lectures, expanded the family library, gathered young people for theatrical performances, initiated the founding of the local museum and bank, and tended to his love of gardening. Meanwhile, Čapek’s mother, a housewife, had an interest in regional folklore, instilling knowledge of folk songs and legends into her children. She read Shakespeare to her children and doted upon her undisputed favorite - Karel. Due to Čapek’s health problems as a child, his mother obsessed over his weak lungs. A curious young boy, he spent time watching local craftsmen and collecting butterflies, beetles, fossils, precious minerals and postage stamps. Čapek's grandmother also lived with the family for a short period, greatly influencing Čapek’s social thinking and language.

Photo Courtesy: Karel Čapek Memorial

Karel Čapek, seated on his mother’s lap, with his brother Josef and sister Helena

STUDENT

“Knowledge is my great and intractable passion; I think I am writing in order to learn to know.” ~Karel Čapek

An excellent pupil, Čapek was the only one of his siblings to attend grammar school in the eastern Bohemian town of Hradec Králové, where he lived with his grandmother. His literary career began early, publishing “Simple Motifs,” “Fairy Tale,” and “Christmas” in the local newspaper when he was only 14. He fell in love at age 15, writing letters to ‘’Anielka,” the daughter of a local music teacher. She inspired him to write poetry, which was first published in a student magazine under a pen name. However, his love went unrequited. He later transferred to the Moravian capital of Brno where his sister lived, after being expelled for taking part in an underground student society. His sister’s husband, František Koželuha, a lawyer, introduced the young Čapek to cultural life, and Čapek started contributing to the Moravian newspapers and magazines. After two years in Brno, his parents moved to Prague where he finished high school, graduating with all A’s. In Prague, he and his brother enjoyed the spirit of modernism. Although shy, they dressed in eccentric cloths, top hats, American-style shoes and walking sticks. His student days at Charles University included semesters at Friedrich Wilhelm University (1901-11) in Berlin and Sorbonne in Paris. While in Paris, he fell in love with Cubism and was inspired by the thinking of French philospher Henri Bergson. His studies culminated with the award of a Master’s degree in Philosophy, having written a dissertation on pragmatism in 1915 at the age of 25.

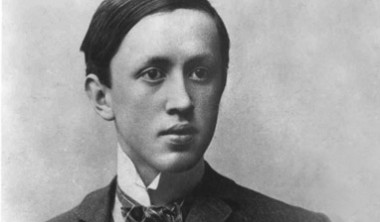

Photo Courtesy: Karel Čapek Memorial

Karel Čapek, 15 years old

JOURNALIST

“Life is easier and more playful the moment we live through something very little. It is rid of tragedy and sorrow. The liberating beauty of little things is the fact that they are insuperably comic.” ~Karel Čapek

Because of spondyloarthritis of the vertebrae, Čapek was exempt from compulsory military service. Due to a shortage in work during the First World War, he served as a tutor to the son of Count Vladimír Lažanský and briefly as a voluntary librarian before returning to Prague to become a journalist. A staunch believer in the individual and supporter of democracy, Čapek’s anti-fascist views were firmly embedded in his writing. As a journalist, he wrote every day, even in candlelight. In 1917, he became a member of the board of editors of the Narod (Nation) magazine, literary and art editor of Národní listy (National Pages), and he wrote a weekly satire for Nebojsa (The Unafraid). He later accepted a job as editor of Lidove Noviny (The People’s Newspaper) on the condition that his brother also would work there. He was also a member of the International PEN and established the Czechoslovak PEN Club, chairing it from 1925 to 1933. Through the PEN Club, he was acclimated with such writers as Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Herbert George Wells, and George Bernard Shaw.

Photo Courtesy: Karel Čapek Memorial

Karel Čapek at his desk

SCIENCE FICTION WRITER

“If dogs could talk, perhaps we would find it as hard to get along with them as we do with people.” ~Karel Čapek

Although not considered a genre at the time, Čapek is best known for his “science fiction” works such as R.U.R., The War of the Newts, and The Insect Play. He introduced the word “robot” to the languages of the world in his 1920s science fiction play R.U.R., which stands for Rossum’s Universal Robots. Suggested by his brother Josef during a brainstorming session, the word robot is derived from the Czech word "robota" or "forced labor.” The futuristic three-act play features nonhumans who revolt, leading to the extinction of the human race. The play was an immediate hit, adding fuel to the public discussion of the 1920s as being the “machine age.” Surprisingly, Čapek considered the play R.U.R the least interesting of all his works, but it brought him the greatest fame. A year after R.U.R.’s release, he collaborated with his brother again on The Insect Play (Ze života hmyzu, 1921), a satire where insects stand in for human characteristics and an allegory on post WWI life. Some of his other renowned works include The Makropulos Affair (Věc Makropulos, 1922), dealing with human mortality, The Absolute at Large (Továrna na absolutno, 1922), presenting a vision of consumer society, and the novel Krakatit (1922), anticipating the invention of a nuclear weapons). Biographers cite his literary heirs to include such prominent writers as Ray Bradbury, Salman Rushdie, Brian Aldiss, and Dan Simmons. Through his writing, he investigated philosophical and political ideas.

Photo Courtesy: Karel Čapek Memorial

Karel Čapek and R.U.R announced in the news

BROTHER

“We´re two, two for everything, for love, life, for a fight and pain, for hours of happiness. Two for wins and losses, for life and for death - TWO!” ~Karel Čapek

Čapek’s brother Josef had a lifelong influence on him. Growing up, the two were seldom apart until 1910, when he went to Berlin as a part of his studies while his brother went to Paris. Upon reuniting in Prague, he penned many of his most known works with his older brother Josef Čapek (1887-1945), who was famous in his own right as an artist and writer. Exploring lighthearted subjects, Karel wrote a year-round guide to gardening, The Gardener's Year (Zahradníkův rok, 1929), with illustrations by his brother Josef. Both authors also enjoyed producing children’s literature. Čapek authored Nine Fairy Tales: And One More Thrown in for Good Measure (1932), which is his collection of fairy tales and one from his brother. Josef’s illustrated series about the Doggie and Pussycat are considered classics of Czech children's literature, affectionately passed down by each generation. The collection of nine charming stories includes How They Made a Cake, How They Found a Doll That Cried Very Softly, and How They Washed the Floor. The two brothers lived to see the political fallout in Europe leading to WWII, with Josef suffering an ill fate at the hands of the Nazis. Josef Capek died in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in April 1945.

Photo Courtesy: Karel Čapek Memorial

Karel Čapek and his brother Josef

FRIEND

“T.G. Masaryk can never lie, not even in a children’s fairy tale.” ~Karel Čapek

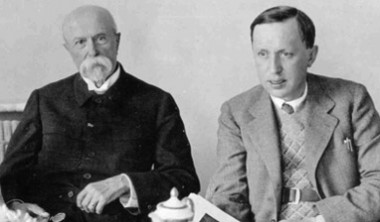

Čapek was politically involved in what was going on in the inter-World War period around him. Soon thereafter, Čapek met the then President of democratic Czechoslovakia, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, who took his American wife’s last name Garrigue, a progressive act for his era. Masaryk became a welcome guest at Čapek’s celebrated debating club, The Friday Men, where the intellectual community met to discuss politics and other important topics. Čapek saw in Masaryk a man of great moral responsibility, character, authority, and intellect. He remained in frequent connection with the President, even visiting him at the Castle. Čapek often defended Masaryk’s views on democracy and interviewed him over several years, publishing Talks with T. G. Masaryk, recording the President’s thoughts on life, politics, and nationalism. Čapek himself took a strong stance in the 1930s against the threat of Germany, ardently condemning fascism. Fearless of the consequences, he felt a deep responsibility to his country. His combination of political and aesthetic concerns was an inspiration for later Czech writers such as Václav Havel.

Photo Courtesy: Karel Čapek Memorial

Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk and Karel Čapek

VISIONARY

“The most terrible struggle in our recent history is being played out. It is not only a struggle for our land, it is a struggle for our soul.... A thousand years of tradition suffice for a nation to learn once and for always these two things: to defend its existence, and with all its heart and all its strength to stand on the side of peace and liberty.” ~Karel Čapek

Fearing the growing power of Germany, Karel Čapek warned against the forces of evil in his works. In the satirical science fiction The War with the Newts (1936), sea-dwelling newts are discovered. In time, the newts demand more living space, a reference to Nazi Germany desiring more “Lebensraum.” With the inevitable war looming, Karel Čapek produced his last play, The Mother (Matka, 1938). The antiwar drama focuses on a mother losing her husband and four sons to war, ending with her sending off her last living son to join the struggle for freedom and humanity, with the word, “Go.” He pled with his country on the imminent danger of war in his essay, “To the Consciousness of the World.” Čapek refused to flee after Czechoslovakia was taken over by Germany in October of 1938, even though he was informed that he was third on the Gestapo’s detainment list. He died at the age of 48 of pneumonia on the evening of December 25, 1938, three months before the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia.

After his death, the prolific American playwright Arthur Miller said, "There was no writer like him…prophetic assurance mixed with surrealistic humor and hard-edged social satire: a unique combination." Čapek was also praised by such renowned writers as Kurt Vonnegut, Milan Kundera, and Stanislaw Lem. A world-class author, he wrote with intelligence and humor. Through his incredible works, he remains an unfaltering advocate of humanism and democracy, a voice of reason and hope even in some of the most difficult times.

Photo Courtesy: Karel Čapek Memorial

Broadcasting the Christmas message of peace, December 24, 1937. Standing, from left, Professor O. Matousek, Karel Čapek, and Professor V. Lesny. Electrical pioneer František Krizik (seated), often called the "Czech Edison," at the time of the peace message broadcasts.

www.mzv.cz/washington