Gregor Mendel

A Farmer's Son

The Czech Republic consists of three regions, prominent Bohemia as well as mineral-rich Silesia and charming Moravia, the birth, study and work places of Gregor Mendel. The humble genius was born into a family of farmers in the tiny village Hynčice in Silesia in 1822. He was the only surviving son, having one older and one younger sister. Recognized as an exceptionally bright students, he was sent to complete high school in Opava, which became a part of a congested industrial area along with the region's capital of Ostrava.

Student

Mendel yearned for knowledge. However, after his father was injured in an accident, young Mendel had to provide for himself in order to continue in his schooling. He managed to earn a "scanty livelihood" through tutoring and his youngest sister gave him a part of her dowry, after coming to terms with the fact that Mendel would not take over the family farm. Enrolling at the Philosophical Institute in the historically ecclesiastical Moravian city of Olomouc, Mendel studied philosophy, ethics, math and physics, taught by Priest Friedrich Franz. Sick from utter exhaustion in making ends meet yet driven by overwhelming deisre to go on with his studies, Mendel was admitted into the powerful Augustinian order, upon graduation and recommendation of his teacher.

Monk

Taking on the name Gregor, Mendel became a monk in 1843 and entered the St. Thomas Monastery in Brno, Moravia. It was a center of intellectual life, where Mendel took special interest in the study of natural an agricultural sciences. Having access to a great library of 30,000 books and top scientific minds as well as food and time, Mendel flourished and was ordained into the priesthood in 1847. He studied agriculture and apple and wine production.

Photo: Gregor Mendel, back row standing second from left

Photo credit: Mendel Museum of Masaryk University in Brno, Czech Republic

Teacher

Albeit appreciating the benefits of the monastery, Mendel was unhappy with his assigned clerical duties in caring for the sick as it took away from his time to study natural science and even made him ill. Aware that Mendel was not fit for work as a parish priest, Abbot F.C. Napp appointed Mendel in 1849 to teach mathematics in the mediaeval town of Znojmo. He was a good, patient, and just teacher and loved by his students. Still, although he tried twice throughout his teaching career, he was unable to pass the state examinations to obtain his teaching license. Luckily, this failure meant that science gained one of its greatest.

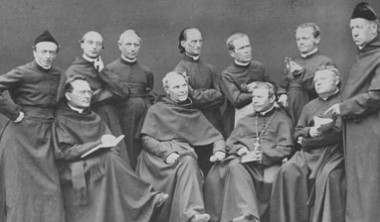

Photo: Members of the Augustianian monastery in Brno. Mendel, in the back row standing second from the right, studies a fuchsia bloom.

Photo credit: Mendel Museum of Masaryk University in Brno, Czech Republic

Scientist

The Abbot sent Mendel in 1851 to the University of Vienna for two years to study among the world’s leading scientists his key interest - natural science. In meeting Professor Christian Doppler, credited for the discovery of the Doppler effect, he learned to apply mathematical analysis to natural events. From Professor Franz Unger, Mendel learned about plant hybrids. Equipped with new knowledge, he returned to Brno and resumed teaching. Moreover, Mendel began his groundbreaking work with green peas. He decided to research how traits are passed from generation to generation, a “question whose significance for the developmental history of organic forms must not be underestimated.”

Photo: Gregor Mendel, front row seated second from right

Photo credit: Mendel Museum of Masaryk University in Brno, Czech Republic

Experimentor

Mendel conducted his experiments in plant hybridization for ten years between 1854 to 1864 in the monastery’s 5 acre garden, testing as many as 28,000 plants, the majority of which were pea plants (Pisum sativum). He spent the first two years preparing by carefully selecting Pisum lines with constant characteristics and concentrated on seven pairs of traits that inherited independently of other traits: smooth vs. wrinkled, yellow vs. green, etc. In the spring, he would use tweezers to pollinate his plants and painstakingly tied tiny sacks around the flower of each plant to prevent cross-pollination. In the fall, he would study the peas, discovering a mathematical pattern. After 8 years, he established the rules of heredity, referred to as Mendelian inheritance.

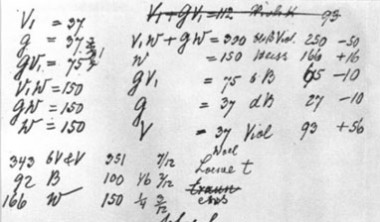

Photo: A page from Mendel's notebook listing crosses between various kinds of beans.

Photo credit: Gregor Mendel and the Roots of Genetics by Edward Edelson

Founder of Modern Genetics

Mendel presented his conclusions twice before the Natural History Society of Brno in 1865. A year later, his paper titled "Experiments on Plant Hybridization" was published in a scientific journal. In it, Mendel demonstrated that traits, in the form of recessive and dominant genes, are passed from parents to offspring and established the Law of Segregation and the Law of Independent Assortment. Although received favorably, no one grasped the significance of his findings. Perhaps because the paper was too mathematical for plant experts or seen as being on plant hybridization than inheritance for others, it went unnoticed for the next 35 years. Today, it is considered seminal work.

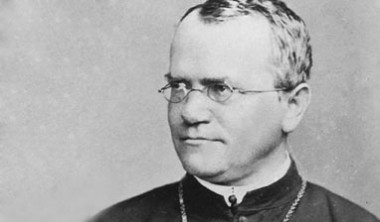

Photo: Gregor Mendel

Photo credit: Mendel Museum of Masaryk University in Brno, Czech Republic

Abbot

Mendel was voted the Abbot of St. Thomas' Abbey in Brno in 1868 upon the death of his predecessor and mentor Abbot Napp. Mendel was humbled to assume the position, thinking he would have more time for his experiments. He also desired the extra income to finance the education of his younger sister’s three sons. Attempting to stay away from the stress of politics, Mendel concentrated on another scientific interest - meteorology. Applying statistical analysis ahead of other meteorologists, Mendel monitored ozone levels as he was interested in its potential for damaging crops. Furthermore, the brilliant scientist also had a keen interest in bees. Referring to them as his “dearest little animals,” Mendel crossbred bees in the 1870s in order to improve honey yields. Mendel’s bee house in the monastery’s garden is the first bee research center in Central Europe.

Photo: Abbot Gregor Mendel

Photo credit: Mendel Museum of Masaryk University in Brno, Czech Republic

Posthumous Recognition

www.mzv.cz/washington